| ||

For us, new countries have been hard, and Greece was more so. But we were braced, if not prepared, and tried to take as good care of ourselves as possible.

| ||

Superfast V at Patras |

After a bit of uncertainty on our way by rail from Firenze -- is this Bologna, or NOT? The other passengers were of mixed opinions, and if there was a sign, it was invisible to us -- we made it onboard the biggest ferry yet, and were shown to a luxurious room. The 20 hour cruise down the Adriatic from Ancona lulled us into thinking Greece would be easy. |

We knew where we were at all times due to the high-tech navigational display on our TV. The food was good enough. And we learned there'd be an easy bus from Patras, our debarcation point in Greece, to Athens, where we hoped to find a hotel. Right up until Athens, it was deceptively smooth. We should have known something was awry... |

navigational television |

In Greece more than in other countries, our travels have been enriched by exchanges with Greeks. This is due in part to the fact that Greece isn't a roman alphabet country -- the alphabet here isn't the roman one we're familiar with, so you often can't figure out where you are or where to go from the signs and clues in the environment, and are forced to ask ...to interact with natives! When I think about the other alien-alphabet countries we've visited -- Thailand, China, Taiwan, Japan -- I conclude that there's a benefit to being stretched linguistically and required to rely more on kindly-disposed natives for advice and direction. How lucky for us that English is the lingua franca!

This train of thought got going as soon as we arrived in Greece -- effectively, when we boarded the Greek-owned SuperFast ferry at Ancona. I immediately started pushing myself to be able to read the signs; this was identified as a high priority after Rochelle led a parade of women into the "uomeni" WC in Firenze -- that would be the men's room. Natives take a peculiar delight in labeling a few key things like bathrooms in the vernacular only and watching the stranieri twitch and err.

Greek becomes a surprisingly friendly language as soon as you realize that many of our words started out Greek. The women's toilet -- I'll spare you the Greek letters -- is labeled "Gynaikon" while the men's, naturally, is "Andron". Of course, here in Greece you need to work out the Greek letters first, and then the sounds of many words make sense. (For more on decoding Greek, I've posted a handy Greek Alphabet page.)

My doomed effort to be able to figure everything out for myself lasted all the way to Athens -- "look, exit is 'Exodus!'" -- where we were ceremoniously dumped on a busy street in an unknown neighborhood in one of the world's most chaotic cities. As the bus blasted off across six lanes of heavy traffic, Rochelle said, "Michael, where's your back-pack?" You know, the essential one with my computer, cables, travelers checks, hairbrush... On the bus, of course! After chasing (and catching) the bus across six lanes of traffic being aggressively used at the time by immensely long buses and jittery taxis, I was breathless and disoriented. Fortunately, we found ourselves next to a restaurant with a menu in Greek and English -- like most Greek menus we've encountered -- and a broken-English-speaking waiter who helped us work out where we were before taking our dinner order.

After a fiasco with Greek Card-phones -- five in our immediate area, all broken -- we worked out why the kiosks along the way each had a coin-operated phone, and managed to get a call out to our friends in Thessaloníki for guidance. Their advice: since all the hotels in Athens are filled by political conventioneers, better find a couple of comfortable looking park benches, or try to get on the night train north. Here's where we got a lesson in the dark side of not speaking any Greek. We managed to wave down a speeding taxi, but when the driver didn't immediately understand our first stumbling attempts to say "train station", "railroad station" in a selection of western European languages, he drove off in a puff of vile exhaust. Frantically, we consulted our three page "survival Greek" primer, which warned us that syllabic emphasis is crucial in Greek, and a misplaced emphasis renders the utterance incomprehensible. Bravely, I steeled myself to say "sidhirodhromikós strathmós" and flagged another taxi. I got about as far as the fifth syllable of the first word and was gathering myself to emphasize the second syllable of the next when the driver said "Train station? Sure. Hop in."

He dropped us off right in front of the unmarked office we needed to enter to arrange for tickets, but we didn't know that, and so we milled around, worked our way through a couple of lines only to find they weren't the right ones, dragged our luggage from one end of the station to the other -- trains not being an important part of the lives of Greeks who plan things, the station in Athens is primitive but under reconstruction -- before finally returning, unbelievingly, to the little unmarked hole in the wall right where we'd started, where a girl was polishing her fingernails while listening to a Nashville Country-and-Western tape. Turned out she was the one knowledgeable person in the whole operation, controlled the berth assignments to the night train, and spoke colloquial English while snapping a wad of pink bubble gum. It was at about this point that we also worked out that we had an hour and ten minutes before the train, not ten minutes as we had feared. We were so happy to have found her that we uncritically accepted her assignment without asking if it was a smoking car. Of course it was! On our second visit we determined that there might be less convenient upper berths in the very full non-smoking car. On our third visit, upon verifying that there was no space in the bedroom car, only in the couchette cars, we arranged for upper berths in a full non-smoking compartment (which means they smoke in the corridor with the door open, which isn't much of an improvement) -- Rochelle has come to call this the "cattle car." But before leaving our gum-snapping C&W-lover, I must give her credit for working with us patiently and in English to make us as happy as possible. With regard to the bedroom car, her advice was brilliant: "Try to find an unoccupied bedroom, camp there, and pay the difference in price when the conductor comes around after the train has started."

Which is exactly what happened, and so rather than endure a night in the cattle car, we did so in an aged German sleeper car vintage 1950, being tossed from end to end of our bunks as the train rattled north through the thick Greek night over the equally aged and decrepit Greek roadbed. We emerged reasonably unbattered (compared to those who spent their nights in the cattle cars), having actually enjoyed a couple of hours of sleep, a bit before sunrise in the Makedonian capital of Thessaloníki -- careful, emphasis on the "ní"; more about the Greek state of Makedonía later, but yes, that's a hard "k", not the soft "c" we usually say, and the emphasis is on the "knee".

We dragged our luggage out of the station and down Thessaloníki's main street toward the "kentro" as advised by the welcome English language signs for our hotel. We had reason to expect a welcome there, because it's owned by our friends ...but that's a story that should also be told, and will in good time. When we arrived, about 6:45, the sleepy night clerk had no room for us yet, and advised us to come back after 10am, which to us seemed like half a day away. This being unacceptable, we wrung an admission out of him that there might be a room ready for us by 8:30, and that the nice restaurant just down the street should be open by now. It was, and the waiter smilingly endured my efforts to order from the Greek side of the menu while studiously pointing to the words I was attempting.

Let me digress for a moment on the subject of attempts by stranieri to communicate in the language of the host country. On all my travels I have stoutly adhered to the principal that by learning some of the language, I offer evidence of my willingness to participate in its life. To say that this approach has produced mixed results over the years would be a rank understatement. In some countries, natives, when confronted by an obvious foreigner, assume that any and all sounds emanating therefrom must be in a foreign language. In Thailand, for example, a feringhi can say something in Thai with absolute correctness and be greeted with a completely blank stare, because the native listener will be straining to understand what language is being spoken, with Thai the least probable of a long list of possibilities. Feringhis simply do not speak Thai; everyone agrees, it is much too difficult. The French are typically not much different in their response, except they do it to their fellow countrymen, too. There are subtle differences in emphasis and pronunciation that reveal whether a speaker is metropolitan (from Paris) or provincial, and a native Cassiddien will never willingly understand a metropolitan utterance (or, it need hardly be added, vice-versa) on the first try. And here's another consistency: males are much less willing to grant that a stranieri's efforts can be understood. Outside of France, if one must speak to a male and there is no shared language other than that of the host country, best to get on to a language both of you speak badly -- I found French more useful and effective in Italy than in France. Women are consistently more willing to strain to understand and to be helpful in correcting mispronunciation. Sienna, whose central-American Spanish is more than adequate, found this to be aggravatingly true in Spain, which is so torn by linguistic divides that it cannot really be said to have a national language.

In a few countries, local conditions and cultural accidents make these rules less binding. In Greece, a surprising number of natives in tourist-exposed work have actually spent time in the United States or other English-speaking country, where they have picked up enough rough-and-ready English, shared the stranieri experience, and love their own culture and language sufficiently to enjoy helping newcomers acquire a little culture. In Taiwan, where English is mandatory in school but the culture makes natives extraordinarily fearful of giving offense by making a mistake, any effort to communicate in Chinese is greeted with great relief: having made the mistake first, face having been lost by the guest, communication can continue on any basis that is possible. In Japan, where education is even more insistent on instilling some English, many Japanese regard a conversation with an English-speaking foreigner as an opportunity to practice and exchange. In Portugal, a long, skinny country surrounded by Spain's linguistic divisions and subject to its own divisive regionalism, any effort to speak Portuguese is regarded as a compliment ...just as it's intended.

The problems seem to crop up most acutely in countries where the natives assign unwonted seriousness to their culture, and use language as a means of discriminating against "uncultured" outsiders. While I appreciate the motivation -- preserving culture is a good thing -- I conclude that in our global village, preserving culture by asserting superiority and exercising and exclusivity seems wrong-headed. The European movement to divide nations into various sub-groups based on geography and local dialect can be productive, in my view, to the extent that the differences are enjoyed, shared, laughed about, and learned from. How delightful that the Provençale language has borrowed or preserved words from the Ligurians who originally occupied their land but have since migrated to north-western coastal Italy! How wonderful that the Belgians, being from a small country surrounded by others who think of themselves as large, simply take pride in learning all the languages and shifting amongst them naturally, appropriating for their own speech the words or phrases from the language that best expresses their thought. In the war of words, aren't they the likeliest survivors? Languages, like every other living thing, get stronger through cross-fertilization and are weakened by inbreeding. When language is used as a means for flag-waving and narrowing the audience, then it stops functioning as it is meant to do, as a means for communication, and becomes every bit as destructive and useless as barbed wire and nuclear missiles.

Before all these thoughts passed through my busy mind, however, our waiter had returned with our tea and orange juice, and light was beginning to come into the sky. Traffic was picking up, revealing Thessaloníki to be a very busy, crowded, alien city -- a Balkan city, to be exact. Even on the short walk back to our hotel, we noticed that the stalls offered a different breed of junk: the expected Greek newspapers, tabloids, nudie magazines, and multi-national candy bars, but also badly-made Russian watches, strange seed and nut confections, camo clothing, pseudo-military boots and "camping" tools. We weren't in need only of a language interpreter, but a cultural interpreter as well.

Luckily for us, our host Atonis (Tony), had decided as a young man that in order to do a good job of running his extended family's hotel, he needed to study marketing in London. Finding that city dismal, he elected to continue his studies at a sister institution in San Diego where he met and after the usual vicissitudes married Taylor, the daughter of a teaching colleague of Rochelle's. Now beset by two young children, Taylor delegated our entertainment to Tony, whom we both instantly adored. Combining the best attributes of an international host (as befits his profession as hôtelier) and an interested elder half-brother (even if he's younger; we were as children in Greece), Tony spent a good bit of his time showing us the ropes as they're rigged here in Greece, then passed us along by way of a friend to a irrepressibly good-humored Cretan named Demitri ... but I'm well ahead of the story now.

In a four star establishment like Tony's in Thessaloníki, one expects the front-house staff to speak adequate English, and the day crew didn't disappoint us, sent us up to breakfast, and promised us a room before 9am. We breakfasted -- best breakfast since Belgium -- and were given a room. We gratefully freshened up, girded ourselves, and went down for our first lesson in travelling Greek at the hands of Tony, whom we had not yet met, and his sister Maria, a travel agent, hoping that they'd turn our Greek experience, which was so far just slightly better than disastrous, around. We arrived moments before Tony, and had already been advised he would be present because his sister wasn't sure enough of her English, so I filled the time by getting her to help me correct my pronunciation of kaliméra. -- good morning -- and epharistó -- thank you. While kaliméra trips easily off the tongue, it took me two stumbling days to get confident enough not to land on the leading "eff" with both feet but reserving the emphasis until the last syllable: ephahristó.

|

a typical Greek church in Thessaloníki

As you can see over the roof of the church, above, Greek architecture is of the stacked concrete cracker box school due, according to Tony, to coming from nowhere with nothing during the fifties. The result, which dominates every settlement, is lamentable in every way except that it did bring the Greeks into a more-or-less modern way of living in a decade -- within a decade from a primitive village existence to a comfortable, if not aesthetically pleasing, western urbanized standard. This is unfortunately the norm for rapidly developing countries. The shame is twofold -- life in these buildings can't be pleasant, and too much is lost in urbanizing a population. Greek cities of any size aren't happy places. |

After getting the professionals started on planning our Greek experience, we plunged into the hurly-burly of this brawling city, looking to learn its rhythms and delights. Each city has its special flavors and patterns, including openness to strangers, and we found this one easy to navigate. We lunched on Yearos -- you may call them gíros. We saw interesting shop windows, and noticed that there are very few good buildings, mostly churches.

elegant shapes from simple materials |

the founding father: Philip II of Makedonía |

On our second day in Thessaloniki, Tony appeared at breakfast, and then minutes later, a slender, intense Greek woman named Zina, who would guide us to Veryína and Phillip of Makedonia's tomb. Who he? Father to Alexander the Great, that's who, and in many ways as much the architect of Alexander's greatness as was Al himself. Phil is widely considered to be the king who first brought forward a notion of unified Greece.

Before him, bumptious warring city states -- Athens, Sparta, Thebes, et al -- had spent all their time and energy feuding. |

Phillip, the second of the name even if the first is not remembered, came on the scene and began assembling a unified and interdependent nation, putting in place infrastructure and bureaucracy to sustain it, and instituting systems of laws and delegation of powers so that the whole would hold together and provide a power base for empire building. Sadly (for him) Phil died in 336 BC after reigning for only a few years. Although I doubt it brought him much pleasure, he was greatly beloved and mourned enthusiastically. His magnificent tomb was set in ancient Aigai, present-day Veryína, the first capital of Makedonia when it was at the shore of the Thermaic gulf. Gradually, as the rich alluvial plain of the Aliakmon, present day Greece's only wholly-owned major river, built the delta further into the gulf, the capital was moved to a new city, Pella, but the burying ground of kings was kept at Aigai because of a prophecy of the Oracle at Delphi that the Makedonian kingdom would hold together as long as its kings were buried there.

Obviously, this place is rich in the founding lore of our culture. Here in Makedonia, the makings of modern Europe can be found, and the site of Phillip II's tomb is surely one of the high holy places. We were thrilled to be brought here.

In modern times, Archaeologists wondered about the contents of the "Great Tumulus" at the village of Veryína, but in the 1970s Greece's political reality calmed down long enough so that a team from the nearby university began excavations. After finding a couple of looted inferior chamber tombs, Manólis Andronícus and his team unearthed the facade of an apparently intact and unlooted tomb of grand details and proportions. Andronícus wrote that instantly he sensed this was the final resting of King Philip of Makedon.

Archaeologists theorize that the tomb was placed here, amongst the rubble of tombs already known to have been looted, and covered over in an effort to divert the attention of tomb robbers ...and, until November, 1977, it worked. Andronicus was so excited by the find, and shortly, so were the Greek authorities, that a special museum was built for its contents in Thessaloníki, and, sadly, Phil's mortal remains were carelessly displayed. In my book, that's barbaric. We were glad to find that Phil's bones are no longer among the artifacts displayed; an even newer museum has been built beneath the tumulus, so that visitors share the experience of "discovering" the Great Tomb and its contents.

Let me lead you through it the way Zina showed it to us, and the way that its discoverer, Manólis Androníkos, unearthed it.

|

artist's rendering of what the tomb looked like before being buried |

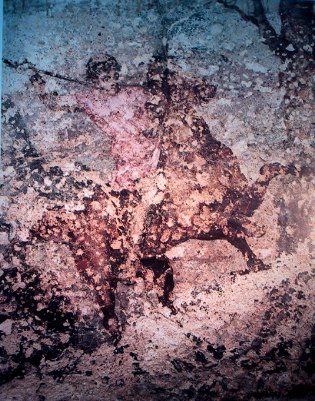

this rider is thought to be Alexander the Great |

The Great Tomb was excavated after having been buried 23 centuries ago among several older tombs and buildings. It is a breathtakingly graceful building possessing in full flower all the classical architectural elements used right to the present day. Above the door, a frieze shows hunters, presumably including Philip and his son hunting.

Remembering that this is a royal chamber burial, and meant to be covered as soon as it was finished, the attention to detail -- a door knocker?!? -- helps us understand that this was a house where a wealthy and powerful man would continue his life in the underworld. |

Encountering this admirable facade and working doors, we might well expect the chambers within to be fitted with all the requirements for gracious living in the year 336 B.C. After puzzling over the frieze -- is one of those purple-wearing royals Phil, and another Alex? Probably, since Phil was gone and the richness of the tomb was meant in part to glorify and legitimize his successor, Al's the one in the middle -- and tinkering with the door for awhile, the excavators entered the outer chamber and found it provisioned more richly than any other such tomb ever found. |

another mounted "royal" |

bathing and storage equipment |

kitchen utensils |

the Queen's larnax |

The tomb contained not one, but two chambers. In the outer chamber, in addition to a generous collection of the necessities of living, there was a golden box, recognizable immediately to the excavators as a larnax or ossuary for the partly cremated remains of ...whom? |

Wife, high priestess, or favorite serving woman? Without knowing who she is, the excavators have come to call her "the Queen". Within her larnax, atop the bones of a woman, a royal wreath, worn on state occassions. By the richness of the golden wreath, she must have been noble herself.

central detail of the Queen's diadem

I especially appreciated the combination of metals, including silver (that sadly doesn't age quite as gracefully as gold) as in the bracelet at right, and some of Philip's jewelry (shown below). |

the Queen's golden laurel wreath

Other precious adornments were found in this outer chamber, jewelry of a type seldom buried except in the case of great respect. These pieces are in excellent condition -- a testimonial to their workmanship and the nobility of gold. The work is beautiful, and exciting as jewelry. In the wreath and the diadem at left, elements are cunningly mounted at the end of springs and wires so that they bobbed and flashed constantly when worn.

silver bracelet with gold clasp

|

Another door, another delay for the excavators. Suddenly the door falls inward, revealing a collection of the warlike artifacts befitting a man, and a larger larnax.

A bigger larnax containing a better wreath and the bones of a man with evident bone damage above the right eye and left leg -- Phil was known to have sustained injuries in warfare in just those places. In the image of Phil at the beginning of this section, notice that his right eyebrow is marked. He lost his right eye in a battle.

|

|

The larnaxes themselves are unimaginably rich: the King's weighs 15 pounds, and his companion's weighs 13. Archaeologists theorize that part of Philip's success was due to his successful use of gold as a means to power. The eight-pointed sun design is associated with King Philip and with his Makedonian regime. |

Within the larnax and atop Philip's bones, his oakleaf crown, obviously battered and burnt, evidently in the cremation fire supervised by experts, according to Zina, who knew just when to stop the fire to save the bones and riches. |

the King's wreath, damaged in the pyre |

a ceremonial neck-piece

King Philip, a formidable and hardy warrior, was nonetheless not a big man, yet he enjoyed "stature" and the affection of his people. Archaeologists theorize that gold was used to aggrandize Philip visually as well as to emphasize the wealth of his domain.

iron-and-gold cuirass didn't help |

Equally rich brooches, cunning pins for holding together clothing, golden shin guards and quiver, a leather-covered iron cuirass (body armor), ceremonial pieces worn by the king to make him shiny and impressive, and still shiny and impressive 23 centuries later.

reconstructed ceremonial shield

Ironically, Philip was assassinated at age 46 during wedding ceremonies for his daughter. Before his death he put his kingdom in such good order, and planned its future so carefully, that his son, Alexander, had a steady platform and a loyal army with which to conquer the known world following his father's plan.

The tomb can be understood as the homage of a grateful son, but also a symbol of the greatness of the dynasty that the young Alexander, and his loyal advisors, intended to extend. |

It is difficult to over-estimate King Philip's reach into modern Greece and indeed into the culture and lives we live today. He undoubtedly invented the gold standard. Classical architecture was developed under his direction.

a fine golden tea strainer

Nor can I exaggerate how thrilling it was to encounter Philip's tomb and grave goods in their original site in Veryína. Later in Greece we would encounter older cultures and their amazing artifacts, but as surely as Philip was descended directly from Zeus, we are directly descended from him. |

golden Medusa emblem

finely wrought detail

Zeus on a coin struck during Philip's reign |

small ivory figures from Philip's trove |

"But I thought Macedonia was a COUNTRY?" | |

|

You thought wrong. Long before "The Republic Formerly Known as Macedonia" -- or whatever the formal name of the new Baltic Peninsula country you were thinking of is (it's actually "the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia" or FYRO Macedonia for short) -- came into being, the part of Greece north of Thessaly, with its capitals at Aigai (now Veryína), then Pella, and now at Thessaloníki (which means "victory over Thessaly") has been called Makedonía. In fact, Philip I of Makedonía, great great grandson of Zeus himself, than whom no one is Greeker, founded Makedonía back in 345 B.C. and used it as the nucleus for what was to become Greece -- before Phil, there was no Greece, only a bunch of feuding city-states.

Residents of Greek Makedonía are quite simply horrified that the upstart ex-communist excuse for a country to the northwest should presume to style themselves with this time-honored Greek name. When this poor recovering commie country was trying to get itself started, and appropriated the name Macedonia (to which it has no historical or geographical claim -- but it does sound good!), the truly Makedonían Greeks next door firmly rejected the nation-building efforts of this pitiful country as long as it used their name. They agreed to recognize the new neighbors and even offered technical and financial assistance on the condition that Macedonia be no part of the new country's name. The diplomats did what they do best, waffled, temporized, and jawboned ... then, unfortunately, let the name Macedonia stick. (Like who's really going to sing a national anthem that starts out "the Former Yugoslav Republic..."?)

Now you might say "What's in a name?" and you might even be right. But if you remind yourself of the troubled past of this region of the Baltic peninsula, you'll understand that the Makedonían Greeks are right in seeing this linguistic incursion as the first step in another effort to winkle this very desirable bit of real estate away from Greece. The FYROs (for want of a better name, in that Macedonia is clearly inadmissible) can't help but notice that their country is landlocked, and heavily dependent on Thessaloniki for port facilities and Greek Makedonia for most of its agricultural supplies.

Try framing the matter in familiar terms. Suppose (1) that we Californians (just go with this train of thought if you're not a Californian, please) had proudly called ourselves Californians for 2.3 millennia because someone named Californicus had united us and built a lasting empire; (2) that the nice folks in, say, Las Vegas, rebelled against their central government last Thursday; and (3) they started a new country and called it California while asserting that their real territorial goals included everything west up to and including San Francisco Bay ...well, you might be upset by their effrontery and fearful for your beloved traditions.

We should always try to walk a mile in the other guy's moccasins, because even if we fail to understand him, we're a mile away and we've got his moccasins!

| |

Happy Ending? for now...25 January 2019

On this date, the Greek Parliament has finally agreed, despite widespread and vocal opposition, to the naming of their northern neighbor “Republic of Northern Macedonia” by a narrow margin of 153 to 146. Greek Prime Minister Alexis Tsipras, posted on social media, ‘Today we write a new page for the Balkans. The hatred of nationalism, dispute and conflict will be replaced by friendship, peace and co-operation.’ to which the Northern Macedonian Foreign Minister Nikola Dimitrov tweeted, ‘courage and hope defeated fear.’ 2 April 2019

The story keeps getting better. Today the BBC tells us that the Greek Prime Minister has traveled to North Macedonia for a love-meet with his North Macedonian opposite number. Here are the boys happily snapping a selfie.  Prime Ministers Zoran Zaev (L, North Macedonia) and Alexis Tsipras (Greece) The Beeb reports, “Tweeting the selfie, Mr Zaev referred to ‘happy moments for an even happier future for the peoples of our friendly countries’.” | |

|

|

originally posted 18 November 2001 : 9:36 Caspar (Pacific) time updated 2April 2019 : 12:05 this site generated with 100% recycled electrons! send website feedback to the Solarnet webster |

© 2001-2019 by Caspar Institute. All Rights Reserved. | |