Venezia

After Greece, Italy was a pleasant change. No more of the mindless ticky-tack, but buildings that looked like someone cared. But there were also unmistakable signs of autumn in the air.

| ||

Venezia

After Greece, Italy was a pleasant change. No more of the mindless ticky-tack, but buildings that looked like someone cared. But there were also unmistakable signs of autumn in the air.

| ||

We had what may have been our best meal of the trip -- judging such things is SO subjective! -- in the unlikely town of Ancona, where our ferry dumped us, and we first noticed the difference between Greek and Italian architecture. At Sot aj archi (93 Via Marconi) we were immediately greeted with that open-hearted suspicion that greets all strangers in untouristed Italy -- Ancona being one of the towns that all the guide books tell you to leave as soon as possible -- and seated in a corner out of the way of the regulars. The best English speaker on the staff was designated our server, and, since there was no menu, we negotiated our meal as best we could.

"You like seafood?"

"Si, si!" we agreed, relieved to be using a language where Yes isn't "Neh!" and thinking ourselves fortunate, since this was clearly a seafood kind of restaurant in a seafood kind of town.

"Fish, or ... er ..." said our sweet server, indicating clams and those classes of sea creatures outfitted with pinchers and sinuous arms.

"Oh, Si, SI!" we insisted.

She then rattled off her diagnosis and headed off toward the kitchen. "I think she said she knows just what to do," I told Rochelle hopefully. And it turned out I was right. In small servings, family style, she brought us a wondrous parade of ocean-going critters: three different kinds of shrimps cooked in three different (and scrumptious) ways, squid salad, another kind of shrimp (I think) that are called "bugs" by the Aussies and chioggi (I think) in this part of Italy.

I should digress for a moment to say that the words for things, especially edibles, vary from what you might want to call "dictionary Italian." In Vernazza, muscoli ripieni means stuffed mussels, even if my Italian-speaking Caspar friends insist that means "ripe muscle-builders." Fresh from Greece we were appreciative of the difficulty in transliterating a word when it's not possible to say, "How do you spell that?" because English and European do NOT share the names of the letters of their shared alphabet. So they might not be "cioggi" at all... You are warned.

Back in our corner table, our server whisked away the cioggi platter, and brought us a plate of smoked salmon with little thin-sliced bits of toast. Next came a plateful of sardines, and then a boat of tiny little clams seasoned lightly with olive oil. Then another boat, this time with little marine snails and two little forks for coaxing the morsels out from the depths of their shells.

Here endeth the antipasti. Next came the primo: spaghetti with a marinara sauce consisting of tomato sauce, more little clams, and some of the little crayfish. After all those appetizers, we were still doing fine, because there wasn't too much of anything, but just enough. Yum. I should note here that to eat a healthy Italian meal one must have at least one antipasto, then a primo piato -- a first course -- followed perhaps by a contorno (like a salad) and then a secondo piato. Skipping any of these steps is considered as unhealthy and potentially life-threatening as, for example, having more than one cup of coffee in the morning. Trying to order a meal without these essentials is likely to disturb the server so much that he or she may simply stop serving you. Once we figured this out, we just relaxed and went with the flow. When in Rome...

The secondo came next: rombo (I think), a sweet white-fleshed fish with reasonable bones in the normal places, served over potatoes with cheese and garnished with roasted tomatoes. I confess that by this time I was not looking for any more food. The single gentleman sitting beside us was making his way through a huge plate of cioggi, clearly a delicacy, and raised his glass to us in recognition of a great meal well tucked away. Forgetting in this moment of intimacy that I was not in a country where everyone speaks English, I blurted, "Wonderful food!"

"Completely delicious, no?" he replied with that effortless European multilinguality we can only admire.

Our server came for the last of the dishes, and raised her eyebrows expectantly. "Due grappi?" I hazarded -- is the plural of grappa, grappas?

Her face lit up with the same mixture of acknowledgement and relief we had encountered with servers elsewhere in Italy, which we loosely translate, 'Phew! They may not know how to talk, but at least they know how to EAT!' "Of course, signor!" and off she hustled, coming back reverently bearing a bottle of colorless liquid. "This is our, how you say...?" and looked to the cultured gentleman at the next table imploringly.

"Ah, yes!" he said. "She wishes you to know that this is their own special house grappa, made with great pride from their own grapes. It is an honor to be asked to share..."

It was indeed delicious, and we did feel honored to share the whole experience.

You might also want to know that this was not our most expensive meal in Italy. With all that wonderful fresh food, wine, grappa, and a generous American-style tip, we got away for $63.

|

Venetian resident helping us feel at home |

The next morning we caught the train to Bologna, and thence to Venezia. We arrived in Venice knowing we had a place to stay, and with our packs filled with dirty clothes, having traveled many days and miles from our last clothes-washing opportunity. Rick Steves guided us to a laundromat two blocks away from the train station, and we happily spent our first hours in Venice laundering and being greeted by a garrulous kitten. |

We vaporettoed to the center of Venice and dragged our bad dogs (our luggage) over "the bridge of sighs." This being one of the most exposed spots in watery Venice, the cold autumn winds blasted us. Thankfully, our hotel was just across and a hundred meters on ...and then up 69 step, narrow steps. We immediately agreed not to buy anything big.

Grey and rainy weather continued throughout our time in Venice, but it neither colored nor dampened our appreciation of the place. |

Grand Canal |

Venezia is a creature of tourism, and as such it is unashamedly and unapologetically commercial. Seventy thousand people still live in the city, but its evolution as an urban center has been arrested for more than a century. We tourists love to see the stately decay; property owners gnash their teeth because they are forbidden to change the outward appearance of their decaying palazzi. By some estimates, half the buildings along the Canale Grande are abandoned. Tourism is heaviest in summer, but it remains heavy even now at the onset of winter, and apparently never sleeps; even now the streets are crowded, and it's hard to imagine how they'd be if narrowed further to the little more than a meter of the wooden sidewalks, without rails, and with up to a foot and a half of water on either side. I am grateful that we arrived during a dry time.

Our advisors were unanimous that the way to experience Venezia was to try to get lost, and so we wandered all over. I never did feel at all lost -- Venice is, after all, a small archipelago of islands connected by innumerable bridges. But wander we did, every daylight minute and plenty of night-time minutes, too. It's an enchanting place.

We stayed in l'Antiquo Locanda Sturion as the proprietors like to call it to draw attention to the fact that there's been a hotel there since 1620. The hotel proudly promotes its “view of the Rialto Bridge and the Grand Canal” -- and it's true; from two of its eight rooms and from the breakfast room, if you put your nose on the glass and crane around to the left, you can see the Rialto Bridge out of your right eye, and the Canale Grande is just outside and five floors down. I could sit happily and watch the boat traffic for hours. The qualities that make Italians such terrible drivers make them fabulous boatmen.

The hotel is wise, and I think a little cynical, to emphasize its longevity and location so enthusiastically. Its proprietors no doubt hope to create a haze of respectable antiquity so we won't notice that in most every other measure of a hotel, it's an expensive disappointment. After humping luggage up a long, narrow stairway (the aforementioned 69 steps), one is greeted by a cheerful and apologetic clerk and given the key to a small, dark, overheated room. Granted, the walls are covered with the same rich cloth as the Palazzo Ducale (Doge's Palace) and there are two small windows that can be opened onto the narrow yet eponymous Calle de Storione.

Almost at arm's length across the alley, one of the decaying and unoccupied buildings is being noisily and doubtless expensively renovated, reminding us that keeping up a building in this marine environment is a difficult and endless task. The Sturion's mattresses may have been changed once or twice since 1620, but they're little better than hammocks. The room is tastefully decorated (if you care about that sort of thing) -- the chandelier is venetian glass; what else? -- but there is one chair and no other place to sit; if you sit propped on your bed with the one pillow available per person, the mattress (I almost want to say pallet) migrates quickly off its steel base toward the Grand Canal. The bathtub is almost four feet long, but there is a bidet. The room is provided with an electric kettle, and the electric plug is thoughtfully hidden behind furniture, and so to boil water one must set the kettle on the floor and crawl around an obtrusive and useless piece of furniture that resembles a large podium to plug it in. Breakfast is packaged cereal, yogurt, condensed orange juice, and yesterday's indifferent Italian pastry -- Italians don't take breakfast very seriously, but they understand that the British do, and this being a place favored by the British, accommodations are made in a half-hearted Italian way. There is internet access, 250 lire the minute, or about $30 an hour, roughly five times the going rate at an internet café. At some point the apologetic clerk will explain that your deposit has been exchanged at an extremely unfavorable rate -- a common practice in hotels, it must be granted, but if you pay in cash, you will be eligible for a discount on the larger-than-expected balance. And one more little thing: the room rate is extortionate: $170 for a room that would cost $125 in San Francisco, another extremely expensive vacation market.

But who cared? Not us! We were in Venice, and the hotel's location is fabulous, provided you don't need to return to your room often. Confine your shopping activities to small, portable purchases -- the steps and smallness of the room are a welcome control on the shopping frenzy that could easily infect any visitor to this romantic tourist mecca. Venezia has been fleecing tourists for centuries. All the guidebooks counsel that you learn your Italian money somewhere else and count your change religiously; one veteran guidebook writer says he is short-changed on average once a day. I doubt if anyone knows how many shops there are in Venice, but certainly more per capita than anywhere else on the planet. Having been so long in the tourist-fleecing business, Venice has actually developed some authentic art forms of its own -- Murano glass, bound blank books, and masks for Carnevale.

There are no bargains in Venice, in part because the maintenance cost of the simplest building is ruinous, but mainly because everything, everything arrives by boat, most of it having been transloaded at least once. And so the case of trinkets that arrives by delivery truck at a shop in Roma, Firenze, or Siena arrives in Venezia after having been unloaded from the same delivery truck in Mestre or at the end of Venice's causeway into a cargo-boat, thence by waterway to a nearby loading point, thence by hand-truck along the narrow "streets" to the shop, adding substantially to its cost. This inflation applies to the goods in the stores, the food for guests and residents alike, the shop fixtures, and the materials required to build and maintain the shop building.

The cost of this isolation from the wheel is high, but the benefit is immediately and pervasively felt. The worst accident that will happen in Venice (provided you don't walk into a canal) is bumping into some fast-moving Venetian cutting a blind corner on foot. The hazards compound if rain threatens, as the Venetians and many of their guests are addicted to umbrellas despite the windy location and narrowness of walkways: watch your eyes! and keep a hand free to bat the umbrellas out of your face. Compared to other Italian cities, the quiet and serenity of a this place without the constant assault of internal-combustion driven conveyances is priceless. Humans, once again the top predator in their environment, can browse, gabble, embrace, gawk, and enjoy their planet without the constant fear and annoyance of vehicular traffic. It is often asserted and probably true that Venetians are the smartest and most cultured people on the planet, and at least in this century the principal explanation for this is their insulation from Henry Ford's curse.

Take away the shops, and there's not much left to Venice. As a great city, it died in the early 18th Century, and has been slowly cannibalizing itself ever since. For anyone interested in the long-term effects of tourism, Venice is a great study. Founded in the time when there was no Italy but for a few great city-states, it used its position in the quietest corner of the Adriatic to create an empire stretching to the then-chaotic east using trade as its principal means of dominion. At the height of its power, in the 14th and 15th Centuries, it absolutely dominated the Aegean basin (as we had seen in Crete) of the Mediterranean and well into the Baltic, building impressive forts, castles, and commercial facilities on every inhabitable promontory and navigable harbor. Bringing the wealth home, it outdid itself with more building, inexorably lining its canals, narrowing its streets, and shrinking its piazzas with tall over-ornamented houses, until almost no open space was available. Without the canals and "rivers" there would be hardly any way to gain perspective in Venezia (and it would be like Firenze.) The striking exception, Piazza San Marco, was carefully ringed and preserved as open space; the way it opens to us after we've navigated the narrow, twisted routes through the city, is powerfully impressive: open space is wealth.

|

courtyard of the Palazzo Ducale

Here we see one of the famous "mouths" through which citizens were invited to drop notes informing on their rivals, neighbors, and enemies. This particular lion's mouth was meant for reporting irregularities in the pricing of grain. Other mouths were for reporting religious, sexual, and doctrinal eccentricities. Toward the end of Venice's primacy, a good share of its bureaucracy was devoted to winnowing these claims and imprisoning or banishing the guilty. |

The Doge's Palace was of course at the top of our list of must-sees, and we got there early the next morning. It's a magnificent old pile, and one wanders through it with one's information wand pressed to one's ear and one's mouth hanging open at the shamelessness of this monument to one of the world's most successful efforts to impress and dominate with wealth.

Official snitch depository |

The city is shaped by two forces besides the sea: its class system, ruled by a burgeoning nobility, and their dogged attempt to preserve their way of life in the face of natural decay, dilution, and dwindling power. For tourists, the effect has been to freeze the city in a late renaissance state. For students of politics, Venice is a master class in how to fail through ossification, and the city's principal sight, the Pallazzo Ducale, or Doge's Palace, is the fascinating epicenter of this failure. Although it is littered with what some critics might term "great art" the intent of almost all of the decoration and indeed the underlying buildings is to glorify Venice's status quo, and to impose it through the ages ... a doomed attempt, but they did get a pretty good run, nearly three centuries!

The effort to secure the status quo and preserve it into the indefinite future is a touchingly human foible that inevitably runs aground on the realities of evolutionary or revolutionary change. To the extent that a small group of benevolent despots can rule a large population of willing workers, the hustle works well, as Venice's empire testifies. Venice dodged the risks of hereditary rule by making the Doge an elective office. Once a nobleman had proven himself worthy, he was elected to this highest office for life ...and this tended to avoid the instability of periodically elected governments. |

the "Employees' Stair" |

The perquisites and appurtenances of power that come down to us in the decaying and incomplete form of the Doge's Palace -- sadly, all but the walls and fixed paintings have somehow vanished -- where we see grand staircases, mighty doors, stately benches for the nobles and a range of less comfortable benches for the visiting rulers, captains, petitioners, dependents, and criminals that came or were summoned to the seat of power. The Palace has an in-house prison and all the necessary mechanisms for summary justice including torture and execution, handy for even the most benevolent despot.

|

There is a well-stocked armory and room for a small standing army, although clearly Venice's masters expected no coup from within the city's boundaries, but did fear, in this city without walls or gates, the possibility of being seized by outsiders. Although the walls are papered with the requisite Christian symbols, the real power here is in the service of commerce.

We know that power corrupts, and absolutely power corrupts absolutely, but of 76 Doges only one ran amok (and after his death his image was duly blacked out in the frieze of doges in the palace's largest room.) What mechanism was set in place to attain such an admirable result? The nobility were the most broadly based aspect of the system of checks and balances that kept the Doge honest: they elected him, and met in counsel periodically to advise and aide him; apparently they had the power to remove him, although this never happened. The most important -- or was it interested? -- of the nobility constituted the official ruling body, the Senate, which met more frequently. A sort of executive committee were drawn from this body based on ability and interest to govern the city's six neighborhoods, its foreign trade, and its agricultural activities on "terra firma" and this "organism" met quite frequently, again to advise and aide the Doge in his governance of the Most Serene Republic. This straightforward mechanism apparently sufficed and indeed flourished for centuries.

The other thing that goes wrong with a privileged class like the Venetian nobility is that it breeds like flies on shit. La Serenissima's willingness, some might even say eagerness, to send whole armadas stuffed full of its sons to wage bloody war in far-flung places around "Mare Nostrum" -- our ocean -- undoubtedly served to keep the numbers under control for a long time, but inexorably the number of nobility got out of hand, and while a few became filthy rich, many more became impoverished. Too many nobles spoil the state. Having been so well served for so long by politics, la Serenissima's first response was to create more bureaucracies, another sort of parallel senate called the Maggiore, another sort of executive committee called the Group of Ten, an advisory organism called "the Censors" ruled by two men to make sure that newly acquired land and serfs in Venetian domains weren't managed too exploitively by impoverished nobles trying to make too much money too fast. Overlapping responsibilities and quarrels over territory increased exponentially, as one might expect, as did the cost of government at a time when la Serenissima's empire was crumbling before Turks who wanted their ocean back. Eventually, the costs and quarrels became more than even the tolerant Venetians could stand, and the republic was melted into a greater Italy along with other powerful city states like Firenze and Roma that had themselves become ungovernable by their original systems.

The Doge's Palace is a power trip in stone, and powerfully impressive nearly three centuries after it fell into disuse. Climbing steps used by the Senators and friends of the Doge -- the even more impressive steps used by petitioners and visitors are too worn to use, but one may stand at their foot and imagine that after walking up between the heroic statues, one might feel small and insignificant -- and sitting on the straight benches in a waiting room where one can deduce from the worn and stained woodwork where thousands of petitioners have awaited their summons for centuries creates a connection with the past that's hard to beat.

|

Saint Mark's lion |

With the exception of a single Bosch panel gifted to the Palace by a wealthy benefactor, the art is surprisingly dull -- possibly it is only the dull lighting and lack of restoration. For a city of 70,000, the cost of maintaining this pile must be staggering. |

The building's external and courtyard facades, recently restored and gorgeous, and some of the ceilings are beautiful, and there are strokes of genius in the architecture: in the great waiting room, the steel rods that keep the roof from pulling apart are concealed in several cases by stiffly straight sculptures, but in several places the rod has been left revealed, gilded, and incorporated as a staff or spear in the grasp of a sculpture.

Venetian rooflines |

ornament conceals structure

Surprisingly, and unlike any similar touristic attraction we've encountered, the Doge's Palace is incredibly poorly documented -- no postcards of the better paintings, ceilings, doors, rooms, statues. And, because there is strictly no picture taking, the imagery that accompanies this page is sparse -- pictures I snuck while the trolls were looking away. |

Although every bit of the building's architecture screams "Venice is Number One; Venice Rules" the building isn't as visual as Gaudi's Sagrada Familia or even Blenheim Palace. Strange.

|

Autumn over the lagoon at Venice |

St Mark's Square |

We happily rode vaporetti and wandered for the rest of our inclement day, stopping for a fabulous lunch and an adequate dinner -- the former in a hidden restaurant unfrequented by tourists. Like Amsterdam, the best sense of Venice, for us, was found on the water-busses, surrounded by polyglot tourists, and here in Venice, by commuting locals. |

I was more impressed by the quality of the light here than in Paris. The cloud-filtered brightness had a pearly quality that made the reds sing and the gilded details glow. Through the befogged and spattered vaporetto windows, accompanied by the babble of passengers, Venice's unreal qualities seemed more real than the rain and the cold. |

Doge's Palace from the lagoon |

|

On our last night, we attended the obligatory Vivaldi concert, ably presented by a small group of superb musicians in a crusty, water stained church near our hotel. On any given night right through the season there are half a dozen of these recitals -- why can't Mendocino do something like that? Culture seems more important than television ...what a concept!

On our last morning, wind blowing from the east had stacked the Adriatic a foot or two higher in the Golfo di Venezia, and the waves are over the lip of some of the lower fondamentas -- pedestrian streets and squares that front the canals and basins. Venezia floods, on average, sixty times a year, sometimes for a few hours, sometimes for days. Aluminum-and-wooden bench-like structures are stacked in essential spots so they can be hastily assembled as walkways when the water rises.

|

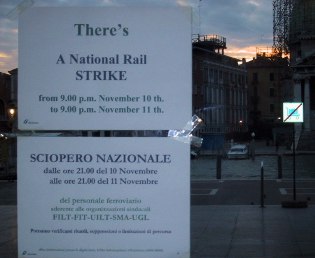

Strike announcement |

We arose at first light, before our hotel could serve us its pitiful breakfast, and vaporettoed back to the station where we found tea (served in real chinaware) and what passes for croissants in Italy. It looked like another grey, miserable day, and so we were not sad to be moving on. |

As soon as our train pulled onto the causeway that connects Venezia to Terra Firma, we could see the sun shining on the Alps away to the north and east. As we rolled across northern Italy, the sun played hide and seek with us. The Alps run like a wall along the richly agricultural top of Italy, never far away from our train's route.

In Milan we boarded an international train bound for Lyon, France's second city, and headed on through Lombardy. Here in northern Italy Autumn had taken all but the last top leaves from the trees. Northwest of Pisa, we wound our way into a gap in the Alps, then turned westward.

|

the Alps on the horizon

We changed trains in Milan's oppressively fascistic central station, built by Mussolini as part of his effort to get the trains to run on time. There was no decent food to be had in the station or anywhere near it -- perhaps the milanese do not eat when downtown; perhaps the architecture spoils their appetites.

The late afternoon sun was gilding the mountaintops, but the valleys were wintry. The buildings looked ...well, Alpine, in a quaint swiss way, reminding us as we rolled into France as the daylight failed that national divisions are recent and accidental in Europe.

After a long train ride, we at last rolled into Lyon in time for dinner, looking forward to the next-to-last chapter of our European adventure. |

|

|

updated 17 November 2001 : 5:08 Caspar (Pacific) time this site generated with 100% recycled electrons! send website feedback to the Solarnet webster |

© 2001-2002 by Caspar Institute. All Rights Reserved. | |