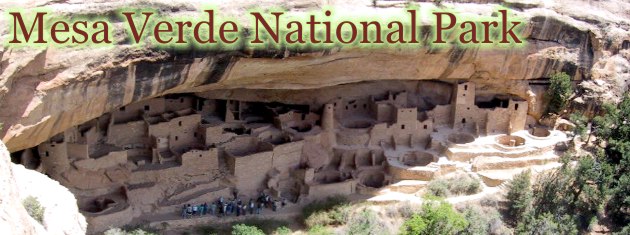

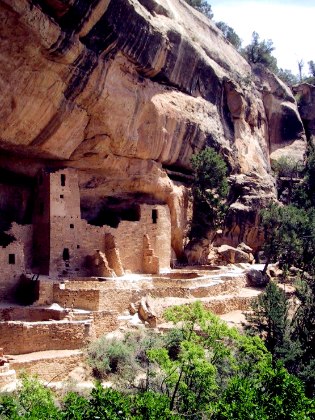

Cliff Palace

Cliff Palace |

The road we took from Taos to Mesa Verde took us across the Rio Grande Gorge again, then over a pass and the Continental Divide and into Colorado, through Durango, across the upper Mancos Valley, and then steeply up the Mesa. |  |

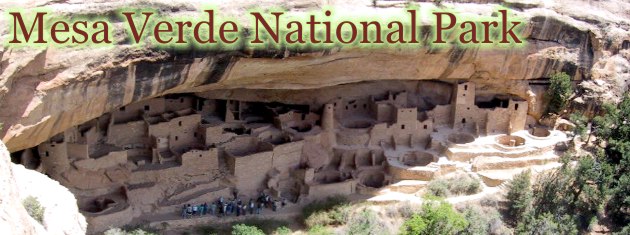

ladder access to Balcony House |

There are three important cliff dwellings at Mesa Verde (and innumerable smaller ones. Rangers here are proud of the fact that this is the richest archaeological site on the continent, and the only National Park dedicated to preserving the works of humans.) The first, Northwest facing Balcony House, a morning visit, was under the direction of a crusty Ranger named Cliff -- where else could he work? The mesa top here is formed by a hundred feet of fine grained sandstone overlying a thin layer of slate through which water cannot percolate. Consequently, water slowly travels through the sandstone, doubtless freezing and dissolving softer layers as it goes, then comes to slate and travels laterally, still dissolving and freezing. |

This loosens large curved blocks of sandstone that fall, forming caves with unpromising rubble-covered slopes and canyons below. Some of these caves are very large, sixty feet deep and more than two hundred feet long at the cliff face. When in use, they were reached by narrow, defensible trails. |

Balcony House spring |

Ranger Cliff explaining |

Nowadays, getting down to the three accessible dwellings is half the fun. Down stairs, past the lower seep-spring at the slate line, then up a ladder and through a narrow crevice behind a granary, to a small but extraordinary cluster of rooms, store-rooms, and two kivas. |

Cliff, it turned out, is an anthropologist from the Texas hill country who's forsaken his homeland and lives on a ranch down in Mancos, the valley below Mesa Verde. Despite crustiness, his ardor for his work is manifest and heart warming. What a job! to be a trained anthropologist assigned to interpret this, the most important concentration of intact ruins on the North American continent.

He told us this is the fifth year of drought here, the worst in recorded history, and pretty much down to the bottom of the reservoir in an outrider range of the Rockies named La Plata the near mountains to the northeast, the first of the Rockies you come to from Four Corners country, where all their water comes from. "What happens next year, we don't even want to talk about. How'd you like that far

|

Cliff explained about the structure of the kivas, circular pit structures of roughly uniform size (about 20 feet diameter) with consistent features: six pilasters ending just far enough below ground level so the timber roof resting on them, and its bark and plaster covering, comes up even with the ground, creating a plaza in a cave where space must have been at a premium.

|

kiva detail at Balcony House |

The size and number of the pilasters is determined by the maximum practical length of the longest available timbers, but like all such uniformities, we expect there were other reasons, too, no doubt including family and clan size and structure.

He noted the firepit, deflector, and ventilation duct, and then explained about the sipapu, which is a hole beside the pit thought to represent the entrance to the underworld to the ancestral Puebloans, the people who built these dwellings. He explained that much of what is "known" is really conjecture, since these dwellings were built during slightly more than one hundred years prior to 1276. In that year, a 23 year drought began -- this can be proven beyond a shadow of a doubt by comparing the tree rings in the vigas that hold up roofs and floors against the unbroken tree-ring record of the southwest that extends back more than a millennium. During the period of that drought, the residents of these splendid dwellings packed up their most precious belongings and left. By 1300, all building had ceased and the mesa was deserted.

Cliff recounted that until 1995, these people were called the Anasazi, which ranger-naturalists interpreted as "Ancient Ones" but which many people, including the Puebloans, knew to be a Navajo word meaning "Ancient Enemies." During an extraordinary period of ecumenical feeling between government rangers and local tribal leaders, someone asked, "What could we do to help make Mesa Verde feel more like your heritage?" "Well," said one Pueblo elder experimentally, with his heart in his throat, "you could stop callings us enemies..." Cliff went on to explain that every year during spring training, the rangers memorize this year's list of politically correct and incorrect terms to use and avoid, and it being early in the year, he hoped we wouldn't be too strict with him.

|

"Face" door and windows |

Since, Puebloan visitors -- now that's a joke, too, since they're really the ones who lived here and we're the interlopers -- have been coming around in increasing numbers, and eager rangers have interviewed them about building curiosities. For example, a member of our group asked, what was this extra-long viga sticking out over the central kiva used for?

|

Well, Cliff ventured, maybe a loom was hung from it during good weather. When he asked this question of a visiting Puebloan elder, he was offered the following explanation: the round kiva represents the Earth-Mother's womb, and the square summer-house above it represents the Sky-Father -- see his mouth is the door and the windows his eyes? -- and so that would be his penis. Or that might just be, Cliff admitted, a Puebloan yanking the leg of a nosy bahana

Regrettably, few modern Puebloans can manage the life of a ranger-interpreter here, Cliff told us. At most, after half a dozen years, they yearn with unquenchable despair to return to the spiritually-based, simple life in the bosom of their clan and tribe. Most often, the yearning comes from confusion between two contradictory value systems, ours of a better car, a new TV, a blonder wife, and the traditional Pueblo-Hopi-Zuñi values that honor our Mother Earth and our Father Sky in a community of mutually supportive like minds. In particular, as we have heard before, alcohol is a menace to "Indians," being metabolized differently and becoming addictive almost immediately.

|

Didn't I tell you, measure twice, cut once?" |

After crawling on hands and knees through the traditional entry to Balcony House, and up a couple of ladders and a stairway pecked into the sandstone cliff, we thanked Cliff and headed to the fine little museum to while away the time before our next appointment.

The 1930s-era CCC dioramas, in particular, are delightful, even humorous. |

In the diorama above, the guy down in the kiva has noted a shortfall between the cut timber and the span between pilasters. There is no doubt at all that long straight timbers were a rarity by the time the cliff dwellings were being built. Indeed, during this period Mesa Verde's people were experiencing a sharp population explosion, and had probably exhausted the resources of the mesa-top. |

kiva ceiling timbering |

Chewed Bread | Recipe: Chewed Bread

Parch a small amount of corn and grind it very fine. Chew this meal until the saliva changes the starch to sugar. Mix chewed meal with more meal until a stiff batter results. Dig a hole in the earth four feet in diameter and a foot deep. Line with corn husks. Pour in batter to a depth of three inches. Cover with corn husks and damp earth. Keep a fire burning over the hole all night. Open the hold, cool the bread, and slice. This sweet, heavy bread serves 32. |

As it turns out, many modern staples originated with native Americans, and the museum makes much of this. For example:

|  |

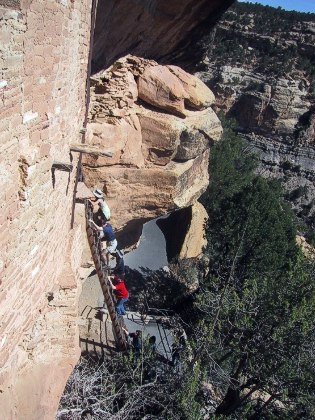

Cliff Palace | |

4-story tower at Cliff Palace |

At Cliff Palace, bumptious Ranger Craig met us. Born in the desert community of Holbrook, he's a native of these parts, and remembers being told, as I was, that in the year 1300 or thereabouts, these Anasazi simply vanished, no one knows where. He says he knew better. I didn't, and the notion of a People simply vanishing seemed so absurd to me that I visualized (and voiced, much to my scientific father's dismay) an absurd scenario in which a big silver Martian mothership scooped them up and whisked them off to a happier planet. |

Where did these 20,000 people go? At Taos Pueblo our guide, a modern Pueblo woman, claimed (and our ranger interpreters today concurred) that most of them headed south and east into the Rio Grande basin, where they founded as many as sixty Pueblos. A few (nineteen) survive to this day. The remainder headed south and west, becoming today's Zuñi and Hopi tribes. |

Cliff Palace watchtower |

Since the Spaniards "pacified" the Pueblos and built churches within the towns, anthropologists don't believe much can be learned from modern Puebloans of their cliff-dwelling past even though the kiva tradition continues strong and the Puebloans have managed to keep their language and culture. It is likely due to the "pacification" and conversion that Pueblo people are so tight-lipped about their traditions and truths.

Dropping in? Yes, that's how it worked and still works: the roof of the kiva is penetrated by a single small-person-sized hole above the firepit, with a long-railed ladder sticking up through it for access -- we saw the tops of these ladders at Taos Pueblo. In most cases, no other entrance was provided, although in some cases kivas had intercommunicating tunnels and "secret" access-ways from other buildings nearby. A very small fire can keep these earth-connected rooms quite comfortable despite bitterest cold (down to ten or twenty below zero Fahrenheit) and even without the first they seldom get down to freezing. Remembering that the "underworld" is where cliff-dwellers' spirits go when their bodies die, and that for these people the underworld was warm, dark, and secure, it is easy to grasp how perfectly the kiva serves as a metaphor. As vernacular buildings go, kivas are also among the most perfectly adapted structures I have ever seen.

In Taos, we were told that Pueblo boys go into the kiva for six months at age nine or ten, to be instructed by the male elders and fed by their mothers. Indeed, a Pueblo male does not allow his "time to be owned by anyone." When in kiva, wife or mother must cook for him; he may only consume food cooked that day. Rendered thus unemployable in bahana society, the women are forced to take jobs, but are often unable to go to work because the "higher calling" -- caring for their men -- supercede. Later, at puberty or later, depending on personal attainments adjudged by the elders, the boys enter the kiva once again, for about a month, and then emerge as men. Our teacher friends Charles and Sakina report that squirrelly boys come out visibly matured by this ...and so, for the boys at least, this works. The girls, however, never enter the kiva during ceremonies, and it is a matter for debate whether they enter at other times, and their ceremonial coming of age is perfunctory.

Between seven and eight hundred years ago in Balcony House and Cliff Palace, the kivas were used as winter houses for the whole family. Looms and matates -- women's tools -- were found in the kivas. The larger alcove named by what Ranger Craig calls the "anthro people" the southern ledge may just have been used for storing firewood. Hopi and Zuñi kachinas

Craig recounted a time when he was on winter "sentry duty" at Spruce House, the largest and most accessible of the cliff dwellings here. He had a thermometer on his coat that registered ten below in the cave, but never dipped below 35 degrees in the one kiva that was rebuilt in 1908 following the last active digging here. Two other kivas at Spruce House have been restored for the use of modern Pueblos, Zuñis, and Hopis who wish to visit their ancient ancestors, who they believe sent their spirits down the sipapus into the underworld underlying this mesa and the whole Southwest. He also remembered guiding a delegation of visiting Navajo traditionalists -- originally Athabascans who migrated to the Southwest in the 15th century for reasons unknown -- and urging them to view the kivas, but these elders declined -- "we have to keep moving" -- because of the power they perceived down the open sipapus.

|

cave apartments |

Other structures in the cliff settlements included small, square summer rooms with remarkably small doors, and in rare cases windows (usually symmetrically arranged above the door to make a face), storage rooms, refuse rooms, and, at Cliff Palace, watchtowers with windows carefully aligned for viewing outposts, possibly lookouts posted across the canyon. There's a sense of protection and preparation for seige, but no evidence it ever came.

At left, the thematic door and window face appears again above a kiva. The counterpoint of round and square structures is pleasing and modern-feeling. |

Compared with the adobe construction at Taos Pueblo, the masonry here is strikingly competent. At other mesa-top sites from earlier eras, one may see the development of this skill. The cave walls themselves were used as part of the structure, and 800 years later the structures are remarkably robust and stable. |

rounded walls |

At right, a wall detail shows how chink stones were pressed into the wet portar to cut down on the volume of mortar (and thus the amount of water) required. |

|

Cliff Palace access |

Original access to the caves was via toeholds and narrow ledge paths, but later, when the threat was understood to be from over-use of resources, more comfortable (but still defensible) access ways were fashioned.

well-used toe holds in the cliff face |

Tower House |

Several other, smaller cliff houses are inaccessible, and Spruce House is a smaller self-guided tour that includes a reconstructed (and decommissioned) kiva that we climbed down in to get a sense of the space -- potentially, very comfortable and ...well, grounded. Within a few hundred meters in one canyon complex, cave dwellings likely housed several hundred ancestral Puebloans. |

The modern building, although completely unobtrustive, is thoughtful and adds to the experience. The ladders, trails, and interpretive signs are excellent. Here's an example of how gently curving trails serve much better than straight pathways. |

curved paths |

There is much evidence that these proto-Puebloans were becoming too successful, life was too good, and population was out of control. The drought may have coincided with devastating deforestation due to overuse of the delicate juniper-piñon mesa-top community. Other communities of the same people, at Chaco Canyon, Hovenweep, and elsewhere also seem to have overshot their support systems at about the same time, with the drought being the final blow. Quite possibly, the ancestral Puebloans were their own worst enemies.

In the present drought, and in the aftermath of the immense fire two years ago, the fragility of the environment was evident to us. On our second day, strong winds from the southwest blew up a sandstorm that made breathing and photography difficult, and after a brief visit to Spruce house and some of the mesa-top dwelling -- no photo-ops due to weather -- we were glad to sit in our room at Farview Lodge and watch the dust storm blow by.

|

looking south from oir room in Farview Lodge |

On the morning of our departure, the air had cleared, and the mesa edge was clearly visible. But we were ready to move on to the Rockies.

|

|

|

updated 1 June 2002 : 7:35 Caspar (Pacific) time this site generated with 100% recycled electrons! send website feedback to the Solarnet webster |

© 2001-2002 by Caspar Institute. All Rights Reserved. | |